BeeKEM

Group Key Agreement with BeeKEM Lets read the BeeKEM code A deep-dive explainer on BeeKEM protocol

See also: Causal TreeKEM Key Agreement for Decentralized Secure Group Messaging with Strong Security Guarantees

Questions:

- Out of stateless agents, stateful agents (groups) and documents, which manage group state with a BeeKEM CGKA? only documents?

- How does delegation work, cryptographically?

pub struct GroupState<

S: AsyncSigner,

T: ContentRef = [u8; 32],

L: MembershipListener<S, T> = NoListener,

> {

pub(crate) id: GroupId,

#[derive_where(skip)]

pub(crate) delegations: DelegationStore<S, T, L>,

pub(crate) delegation_heads: CaMap<Signed<Delegation<S, T, L>>>,

#[derive_where(skip)]

pub(crate) revocations: RevocationStore<S, T, L>,

pub(crate) revocation_heads: CaMap<Signed<Revocation<S, T, L>>>,

}GroupState as set of Delegations and Revocations

(DelegationStore is a ‘Content Addressed’ Map (HashMap where hash is of content) of signed delegations - seems like same type as delegation_heads tbh)

What is a delegation?

pub struct Delegation<

S: AsyncSigner,

T: ContentRef = [u8; 32],

L: MembershipListener<S, T> = NoListener,

> {

pub(crate) delegate: Agent<S, T, L>,

pub(crate) can: Access,

pub(crate) proof: Option<Rc<Signed<Delegation<S, T, L>>>>,

pub(crate) after_revocations: Vec<Rc<Signed<Revocation<S, T, L>>>>,

pub(crate) after_content: BTreeMap<DocumentId, Vec<T>>,

}So the proof is, potentially, another delegation, and this would be used in an invocation

revocation is

pub struct Revocation<

S: AsyncSigner,

T: ContentRef = [u8; 32],

L: MembershipListener<S, T> = NoListener,

> {

pub(crate) revoke: Rc<Signed<Delegation<S, T, L>>>,

pub(crate) proof: Option<Rc<Signed<Delegation<S, T, L>>>>,

pub(crate) after_content: BTreeMap<DocumentId, Vec<T>>,

}the delegate is an Agent, can can is Access, which is very simply:

pub enum Access {

/// The ability to retrieve bytes over the network.

///

/// This is important for the defence-in-depth strategy,

/// keeping all Keyhive data out of the hands of unauthorized actors.

///

/// All encryption is fallable. For example, a key may be leaked, or a cipher may be broken.

///

/// While a Byzantine node may fail to enforce this rule,

/// a node with only `Pull` access does not have decryption (`Read`) access

/// to the underlying data.

Pull,

/// The ability to read (decrypt) the content of a document.

Read,

/// The ability to write (append ops to) the content of a document.

Write,

/// The ability to revoke any members of a group, not just those that they have causal senority over.

Admin,

}and Agent is

pub enum Agent<S: AsyncSigner, T: ContentRef = [u8; 32], L: MembershipListener<S, T> = NoListener> {

Active(Rc<RefCell<Active<S, T, L>>>),

Individual(Rc<RefCell<Individual>>),

Group(Rc<RefCell<Group<S, T, L>>>),

Document(Rc<RefCell<Document<S, T, L>>>),

}What is Active? “The current user agent (which can sign and encrypt).”

I’m not sure why Delegate has ‘after_content’ and ‘after_revocations’…

in group we also have:

pub enum MembershipOperation<

S: AsyncSigner,

T: ContentRef = [u8; 32],

L: MembershipListener<S, T> = NoListener,

> {

Delegation(Rc<Signed<Delegation<S, T, L>>>),

Revocation(Rc<Signed<Revocation<S, T, L>>>),

}which is interesting… like this is the abstraction over both delegation and revocation and kind of indicates to me that this is a… well maybe hopefully(?) a DAG? of operations

linking to previous delegations, revocations…

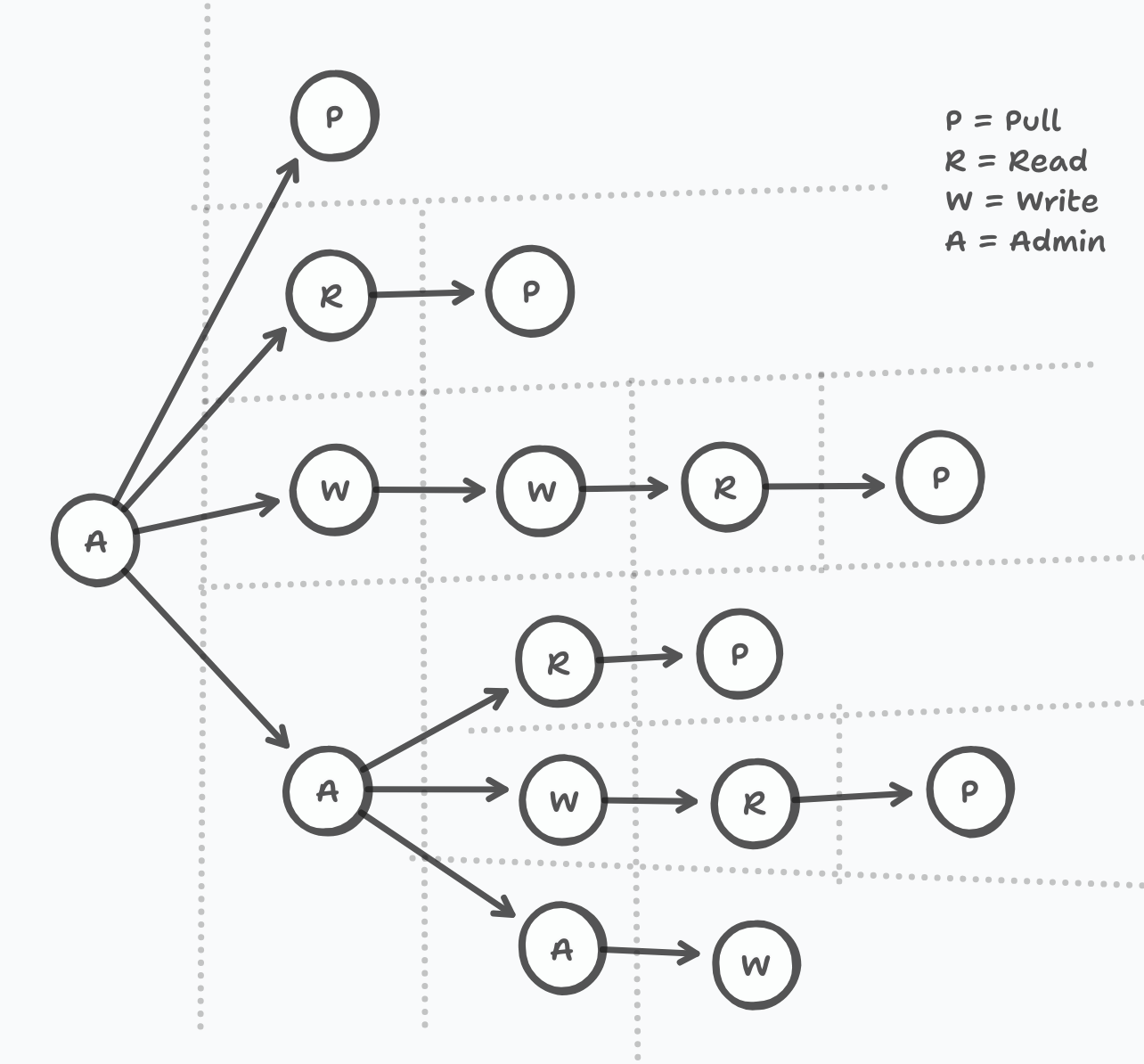

Actually the delegation proof chain is more like a tree, cos there is no point having multiple proofs. but from the perspective of any principal it even doesn’t really need to be represented as a tree, more just as a linked list. (Dotted lines represent the boundary between different principals)

we don’t bother setting up a CGKA because maybe we don’t need to encrypt these delegations? it’s like… this is the metadata that would be seen anyway. but everything IS signed and hashed which is the main relevant cryptography here.

my next question is what is ‘after_content’? BTreeMap<DocumentId, Vec<T>>,

what is the Vec<T>?

T: ContentRef = [u8; 32],

pub trait ContentRef: Debug + Serialize + Clone + Eq + PartialOrd + Hash {}

impl<T: Debug + Serialize + Clone + Eq + PartialOrd + Hash> ContentRef for T {}ContentRef is a trait that meets all these bounds, what is it tho?

Divergences from TreeKEM

- Concurrent deletes and updates means delete always wins? Or maybe this is same as TreeKEM

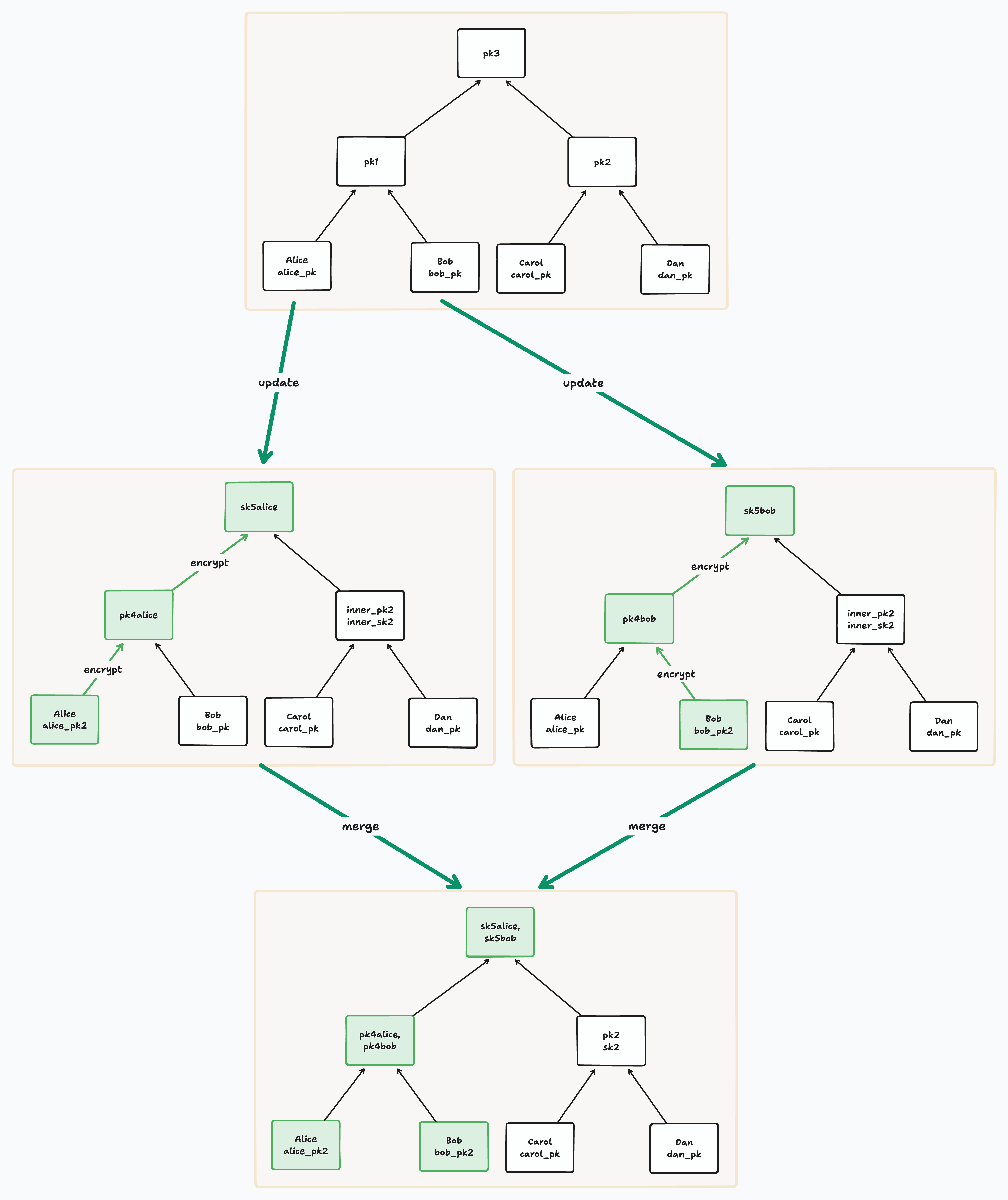

BeeKEM has a notion of ‘conflict nodes’. This is where multiple members have tried to concurrently write to the key material of a node. Rather than resolving the conflict in some destructive way, like throwing away one of the updates, BeeKEM keeps both - only adding new information, not deleting any, until a new causally subsequent update (i.e. one that references the conflicted state) puts the node out of conflict.

This means that for BeeKEM we update the definition of the “resolution of a node” to mean either (1) the single DH public key at that node if there is exactly one or (2) the set of highest non-blank, non-conflict descendents of that node.

If we merged in both sides of a fork, then we know we’ve updated both corresponding leaves with their latest rotated DH public key. Since taking the resolution skips all conflict nodes, it ensures that we integrate the latest information when encrypting a parent node. That’s because any non-conflict nodes have successfully integrated all causally prior information from their descendents.

This means an adversary needs to compromise one of the latest leaf secrets to be able to decrypt an entire path to the root. Even knowing outdated leaf secrets at multiple leaves will not be enough to accomplish this. An honest user, on the other hand, will always know the latest secret for its leaf.

How does decryption happen when a node is conflicted?

In this scenario, is there a group key?

BeeKEM is our variant of the [TreeKEM] protocol (used in [MLS]) and inspired by [Matthew Weidner’s Causal TreeKEM][Causal TreeKEM]. The distinctive feature of BeeKEM is that when merging concurrent updates, we keep all concurrent public keys at any node where there is a conflict (until they are overwritten by a future update along that path)==. The conflict keys are used to ensure that ==a passive adversary needs all of the historical secret keys at one of the leaves in order to read the latest root secret after a merge.

Leaf nodes represent group members. Each member has a fixed identifier as well as a public key that is rotated over time. Each inner node stores one or more public keys and an encrypted secret used for (deriving a shared key for) decrypting its parent.

During a key rotation, a leaf will update its public key and then encrypt its path to the root. For each parent it attempts to encrypt, it will encounter one of a few cases:

- In the “normal” case, the child’s sibling will have a single public key and a corresponding secret key. The child uses the public key of its sibling to derive a shared Diffie Hellman (DH) secret. It then uses this shared DH secret to encrypt the new parent secret.

- In case of a blank or conflict sibling, the encrypting child encrypts the secret for each of the nodes in its sibling’s resolution (which is the set of the highest non-blank, non-conflict descendents of the sibling). This means a separate DH per node in that resolution. These encryptions of the secret are stored in a map at the parent.

Let’s have a look at the beekem.rs code:

The root is an InnerNode.

Here’s how to define a BeeKEM tree with two leaves using the provided code:

Tree Structure (2 leaves):

3 (root - InnerNode)

/ \

0 1 (leaves)Code to Create the Tree:

use crate::{

crypto::share_key::ShareKey,

principal::{

document::id::DocumentId,

individual::id::IndividualId,

},

};

// 1. Initialize required IDs and keys

let doc_id = DocumentId::new(b"example_doc_id"); // Replace with actual doc ID

let member1_id = IndividualId::new(b"member1"); // Replace with actual ID

let member2_id = IndividualId::new(b"member2"); // Replace with actual ID

// Generate keys for members (in practice, use proper crypto)

let member1_pk = ShareKey::generate(&mut rand::thread_rng());

let member2_pk = ShareKey::generate(&mut rand::thread_rng());

// 2. Create the tree with first member

let mut tree = BeeKem::new(doc_id, member1_id, member1_pk)

.expect("Failed to create tree");

// 3. Add second member

let member2_leaf_idx = tree.push_leaf(member2_id, NodeKey::ShareKey(member2_pk));

// Now the tree has:

// - Leaves at indices 0 (member1) and 1 (member2)

// - Root inner node at index 3Key Properties:

-

Leaf Indices:

0: First member (member1_id)1: Second member (member2_id)

-

Inner Nodes:

3: Root node (only inner node in this tree)

-

Tree Math:

assert_eq!(tree.tree_size, TreeSize::from_leaf_count(2)); assert_eq!(treemath::root(tree.tree_size), TreeNodeIndex::Inner(InnerNodeIndex::new(3))); -

Path Examples:

- Member 0’s path to root:

[0 → 3] - Member 1’s path to root:

[1 → 3]

- Member 0’s path to root:

Does BeeKEM tolerate network partitions as well as DCGKA? If so is there a novel innovation here that makes O(log n) updates still possible?

For CGKA, we have developed a concurrent variant of TreeKEM (which underlies MLS). TreeKEM itself requires strict linearizability, and thus does not work in weaker consistency models. Several proposals have been made to add concurrency to TreeKEM, but they either increase communication cost exponentially, or depend on less common cryptographic primitives (such as commutative asymmetric keys). We have found a way to implement a causal variant of TreeKEM with widely-supported cryptography (X25519 & ChaCha). There should be no issues replacing X25519 and ChaCha as the state of the art evolves (e.g. PQC), with the only restriction being that the new algorithms must support asymmetric key exchange. We believe this flexibility to be a major future-looking advantage of our approach. Our capability system drives the CGKA: it determines who’s ECDH keys have read (decryption) access and should be included in the CGKA — something not possible with standard certificate capabilities alone. Keyhive Repo - Design

Hey @alexg and @Brooke Zelenka, I’ve been trying to wrap my head around BeeKEM over the last few days and have something I’d love your help understanding: In beekem.rs where the comment says:

During key rotation […] In case of a blank or conflict sibling, the encrypting child encrypts the secret for each of the nodes in its sibling’s resolution (which is the set of the highest non-blank, non-conflict descendents of the sibling). This means a separate DH per node in that resolution. These encryptions of the secret are stored in a map at the parent.

What do blank and conflict siblings respectively represent? I can vaguely guess at how, due to concurrent operations, a node might have none or multiple IDs/keys assigned to it, but it feels kind of tricky for me to grasp how exactly it happens. I’d also love to know if Keyhive retains the concept of proposals and commits from MLS - guessing not

Me getting distracted

Here’s a quote from Weidner et al.:

MLS allows several PCS updates and group membership changes to be proposed concurrently, but they only take effect after being committed, and all users must process commits strictly in the same order. A proposal also blocks application messages until the next commit. In the case of a network partition […], it is not safe for one subset of users to perform a commit, because a different subset of users may perform a different commit, resulting in a group state inconsistency that cannot be resolved. As a result, MLS typically depends on a semi-trusted server to determine the sequence of commits. There is a technique for combining concurrent commits [ 8 , §5], but this approach does not apply to commits that add or remove group members, and it provides weak PCS guarantees for concurrent updates. (Section 3)

Wait, what are proposals and commits? Commits are what we’ve been talking about - operations on the group state. Proposals are essentially just a way, in MLS, of pre-checking with the server if a commit will be allowed: is it well-formed, does it conflict with any (server-set) policies, and possibly checking with other group members if they approve the change too. But hold on - did it say application messages get blocked? Multiple LLMs tried to mislead me on this so for clarity:

Some operations (like creating application messages) are not allowed as long as pending proposals exist for the current epoch. OpenMLS Book - Committing to pending proposals

What does it mean that if a subset of users performs a different commit, there will be a state inconsistency that cannot be resolved?

Proposals and commits aren’t, from what I can tell, part of BeeKEM, so just going to leave that question for another time.

BeeKEM

Definitions

encrypter child: the child node that last encrypted its parent.

inner node: a non-leaf node of the BeeKEM tree. It can either be blank (None) or contain one or more public keys. More than one public key indicates the merge of conflicting concurrent updates. Each public key on an inner node will be associated with a secret key which is separately encrypted for the encrypter child and all members of that encrypter child’s sibling resolution.

leaf node: the leaf of the BeeKEM tree, which corresponds to a group member identifier and its latest public key/s. A leaf node can also be blank (None) if either (1) it is to the right of the last added member in the tree or (2) the member corresponding to that node was removed (in this case, the blank functions as an implicit tombstone).

ownership of a tree: you own a tree if you can use it to encrypt a new root secret. An owner will correspond to one of the members of the tree group (and hence one of its leaves).

resolution: either (1) the public key/s of a node or (2) if the node is blank or contains conflict keys, all of its highest non-blank, non-conflict descendants’ public keys. The resolution is never taken at the root, so the worst case resolution is the n / 2 leaves of one of the root’s child sub-trees if all of that sub-tree’s inner nodes are blank or contain conflict keys.

Invariants

- A group will always have at least one member. Hence, a tree will always have at least one non-blank leaf.

- In a subset of operations, concurrent adds and removes must be ordered last (because they blank inner nodes).

Properties that must be ensured by Keyhive

- Causal ordering (and receipt) of CGKA operations.

Public Key invariants

- After a node is updated and a new secret encrypted, it will have a single public key (corresponding to that new secret).

- A node encrypting its parent will always have a single public key. That’s because

- you can only encrypt starting from the leaf you own,

- the leaf you own will always have a single public key in your copy since you will always have all causal predecessors and will have written the latest one, and

- each parent you encrypt up your path will have a single public key after encryption.

- A node might have multiple conflicting public keys if concurrent updates from other members are merged into your tree. Each public key corresponds to a separate secret key.

Notes

- A root secret will always correspond with a specific key rotation (update) at one of the leaves.

- After a merge of two concurrent operations, the tree will no longer have a root secret.

GPT Take

BeeKEM is basically TreeKEM with a big “keep-all-the-concurrent-keys” twist. Here’s the nutshell:

- Conflict handling

- TreeKEM: Whenever two people rotate keys at the same time, one update wins (or you have to roll one back). You don’t keep the “losing” public keys around.

- BeeKEM: If two leaves update concurrently, any inner node that sees conflicting siblings will stash all the new public keys there (in a

ConflictKeys), rather than throwing any away.

- Merge semantics

- TreeKEM: Not designed for true concurrent merges—you end up serialising updates or running an external merge protocol.

- BeeKEM: Built for causal merging. The

apply_pathmethod will deterministically merge concurrent adds/removes by sorting new leaves and blanking old paths, and inner nodes merge their secret stores instead of clobbering them.

- Security guarantees

- TreeKEM: Security reduces to the last writer wins; a passive eavesdropper needs only the latest secrets on one path.

- BeeKEM: A passive adversary must compromise every historical secret key on some leaf in the merged history in order to derive the current root key—because you’ve kept every concurrent public key around until it’s explicitly overwritten.

- Complexity trade-off

- TreeKEM: More lightweight—only one key per node, minimal state.

- BeeKEM: Inner nodes can blow up in size if you get lots of concurrent updates, since each conflict resolution may add multiple DH‐encrypted secrets to the

SecretStore.

- Use cases

- TreeKEM: Best for mostly sequential groups (like typical MLS), where you can live with O(log n) updates and simple path encryption.

- BeeKEM: Better when you expect high‐concurrency, offline edits, or want to merge membership ops without coordination. In short, BeeKEM = TreeKEM + causal merge + “keep every conflict key” → stronger merge guarantees at the cost of bigger nodes and more DH operations.

In Code

Here are the hotspots where BeeKEM veers away from a vanilla TreeKEM implementation:

Conflict‐tolerant inner nodes

In SecretStore, inner nodes carry multiple encrypted secrets (one per conflicting public key) rather than a single key.

Look at encrypt_new_secret_store_for_parent (around the sibling‐resolution logic): it iterates over every node in the sibling’s resolution and sticks all those DH encryptions into the secret_map.

if sibling_resolution.is_empty() { … } else {

for idx in sibling_resolution {

let encrypted_sk = encrypt_secret(…);

secret_map.insert(idx, encrypted_sk);

}

}

SecretStore::new(new_parent_pk, child_pk, secret_map)That “multiple inserts” is pure BeeKEM.

Keeping conflict keys around

In should_skip_for_resolution (and its use in append_resolution) you’ll see how blank or conflicted inner nodes get expanded into their children, rather than treated as “one key or nothing.”

fn should_skip_for_resolution(&self, idx: TreeNodeIndex) -> bool {

match idx {

TreeNodeIndex::Inner(i) => self.inner_node(i).as_ref().is_none_or(|n| n.has_conflict()),

_ => …,

}

}Merging concurrent updates

apply_path is where BeeKEM actually merges two paths. Instead of overwriting, it calls:

current_node.merge(node, &removed_keys_set);That merge call (on both LeafNode.pk

via NodeKey::merge and on SecretStore::merge) folds in both sets of keys.

Deterministic add/remove ordering

In sort_leaves_and_blank_paths_for_concurrent_membership_changes, BeeKEM will blank out and then re‐push concurrently added leaves in sorted order. TreeKEM simply fails or serialises—you won’t find anything like this in the original spec.

Root‐key ancestry tracking

The field current_secret_encrypter_leaf_idx plus the LCA logic in decrypt_tree_secret lets BeeKEM handle decryption over a merged, branching history. TreeKEM just assumes a single writer path.

Every one of those pieces—multi‐encrypt in encrypt_new_secret_store_for_parent, conflict resolution in should_skip_for_resolution/append_resolution, merging in apply_path, and the leaf‐sorting logic—are where BeeKEM departs from the one‐writer, one‐path TreeKEM design.